Silver, Salts and Shadows

Left image

Right image

Text

Silver, Salts, and Shadows

By John Minihan

‘I have seized the light,’ cried Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre upon producing the first daguerreotype in 1839, a small, silver-coated copper plate on which he and his camera had captured and fixed an image from life. Daguerre had inaugurated the age of photography. From daguerreotypes to ambrotypes to paper prints, it all happened with surprising speed.

In 1962 I was an apprentice in the London Daily Mail darkroom. My job was to replenish the paper lockers with Kodak and Ilford printing paper of various grades, make up fresh chemicals to the correct temperature, process hundreds of rolls of black and white film, both 35 mm and 120 mm, and copy on glass plates other images from around the world. I loved the magic of seeing an image appear before my eyes. There is a generation of photographers who don’t know the alchemy of the darkroom. Photographers would give me their film to process and contact: I loved that whole tactile world of making photographs.

It was also the time I became aware of nineteenth-century photography, in particular the photographs of Julia Margaret Cameron, Nadar and Eugene Atget. But it was the 1960s, the miniskirt, rock ’n’ roll and the Vietnam war, with great picture magazines like Life and Paris Match using spreads in graphic colour and black and white of the Vietnam war by Don McCullin and Larry Burrows with their Nikon F cameras slung over their shoulders – they were heroic figures who have left enduring images we should never forget. Facebook last year tried to remove an iconic image by photographer Nick Ut, of nine-year-old Kim Phuc fleeing a napalm attack in Vietnam in 1972. Under global pressure the founder of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, caved in and the photograph was reinstated.

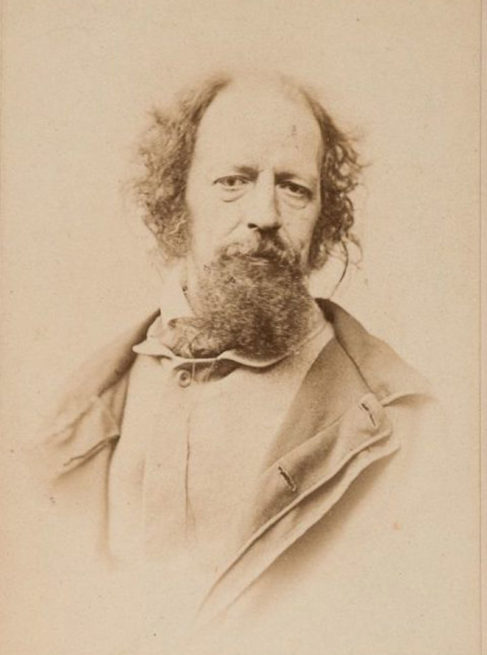

However, I was interested in the work of Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–79) and her amazing images of women with classic profiles: scholars, poets, philosophers, scientists, artists, the elite of the Victorian world passed before her eyes and posed in front of her camera. They had to be still for minutes at a time. In many of the mother-and-child photographs the women had a Madonna-like expression. Among her more famous frequent models was the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson. What a marvellous subject for Cameron’s camera, one of the most celebrated poets ever to write in English. His life corresponded to the high age of photography. Charles Darwin visited Cameron’s home at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight to have his photograph taken, as he, like Tennyson, was fascinated by photography. But it’s through the images of Julia Margaret Cameron that we know them. As a collector of photography I have a carte de visite photograph of Tennyson, sadly not by Cameron.

In the early 1960s photography began to be considered a legitimate form of expression rather than an ingenious courtesy sitting. It is now 178 years since Louis Daguerre cried out from his balcony, ‘I have seized the light.’ Paris became the ‘city of light’, home to artists, writers, photographers and jazz musicians. Many from the United States found the freedom to express themselves through their music. Paris breathes images for me. I have always loved Eugene Atget’s (1898–1927) photographs. They are among the greatest images made of Paris at that time: townhouses, streets, working people, gardens, statues, musicians, bedrooms, granite drawing rooms; there are many notable Atget photographs which will never leave me. Paris of the 1920s and 1930s has been immortalised by many great photographers: Man Ray, André Kertész and his fellow Hungarian Brassaï, not to mention Henri Cartier-Bresson; writers like James Joyce and his friend Samuel Beckett lived in Paris and were part of its literary tradition. ‘Paris is a moveable feast,’ Ernest Hemingway famously wrote. No city in the world has been so much photographed or written about – its very name is a love song.

Last year I visited Paris where I spent my seventieth birthday to see the exhibition at the Petit Palais on Oscar Wilde (1854–1900). The entrance was adorned with a large photograph of Wilde taken by the American photographer Napoleon Sarony (1821–96) on Wilde’s first visit to the US in 1882. There are other masterful images of the Wilde family, among them a beautiful study of Wilde’s wife Constance holding their son Cyril taken by Henry Herschel Cameron, the younger son of Julia Margaret Cameron, in 1889. The show was curated to a great extent by Wilde’s grandson Merlin Holland, whom I photographed along with the actor Sir John Gielgud in London in 1995 as they unveiled a plaque to honour Oscar Wilde at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. Wilde visited Paris with his mother as a teenager, spent his honeymoon there and died in a cheap hotel now named L’Hotel, 13 rue des Beaux-arts. The Oscar Wilde room is still available to those who want to recite his famous last words, ‘This wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has to go.’

When I visit Paris I will have a drink at one of Wilde’s favourite haunts, the Café de Flore on Boulevard St Germain, and with my Rolleiflex take photographs of Wilde’s grave by Epstein in Père Lachaise. Wilde, like Marcel Proust, loved to look at photographs. Most writers do: there’s nothing quite like them for communicating a sense of the past. The Victorian photo albums lovingly adorned with flowers give us a rare glimpse into the lives of a family, memories which glow more brightly with the passage of time. The album inspired universal fascination, with pictorial representation of a diverse array of cultural activities, from cycling to amateur dramatics, sports and just dressing up the children for the camera.

The truth value of photography was an important part of its overall meaning. Collections of photographs in an album performed many more functions and possessed wider meanings than any single picture could. Photography has profoundly influenced the way we look and think about the world. Technological innovation in the digital world has blown away the past which was familiar to me: film, chemicals, darkrooms, just touching a photograph with its captions and the stamp of the photographer on the back. Yes, a computer can mimic a photograph, but the smell, the aura has gone. When I walk anywhere with my Rolleiflex camera around my neck people are always curious and want to ask about the exquisite machine. I tell them it’s all about mirrors and magic.